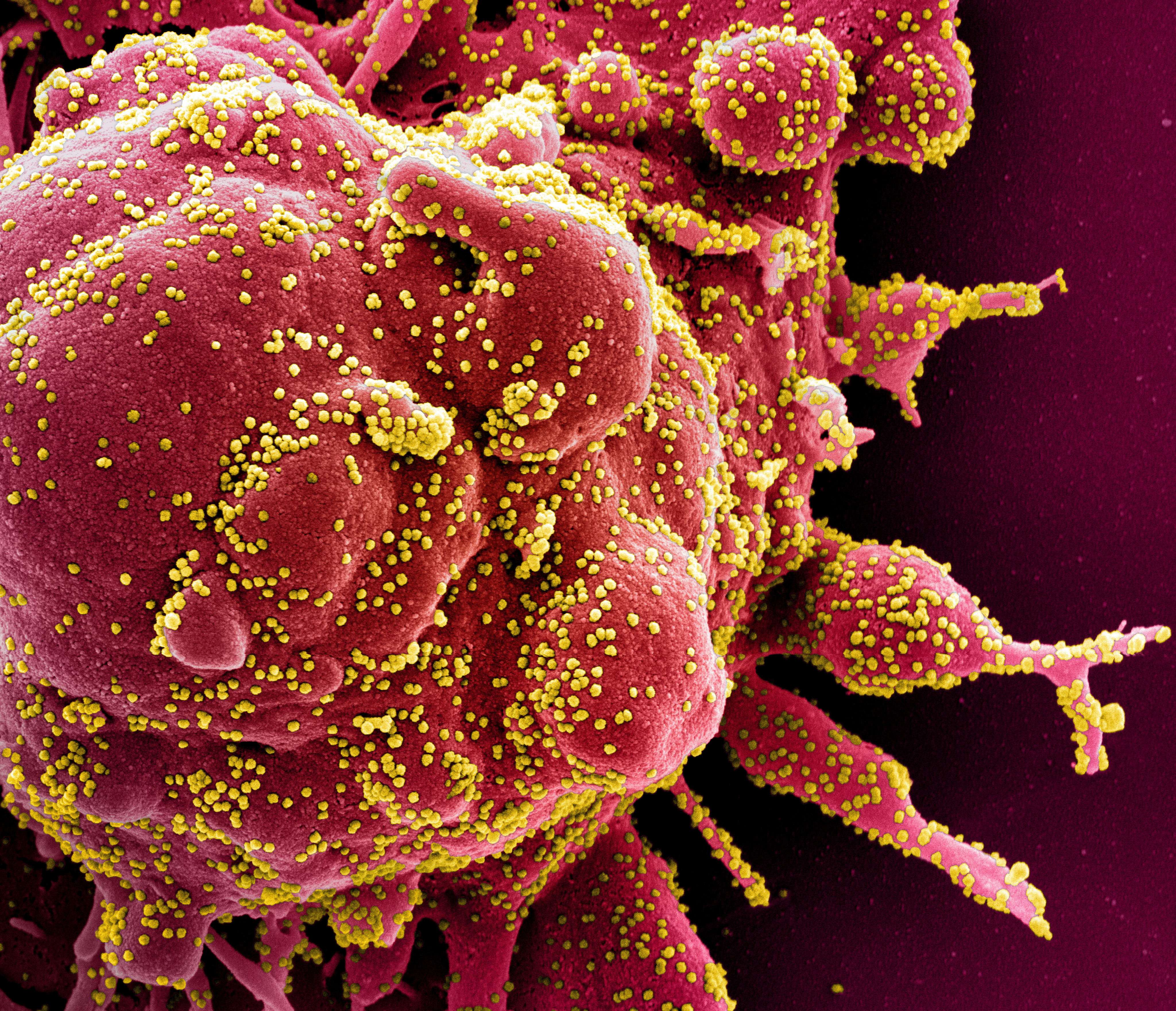

The COVID-19 It has already infected more than 630 million people and caused more than 6.5 million deaths. And nearly three years after he arrived on the planet, there are still many unknowns. It is suspenseful to know what it is The origin of the virus Which causes the disease: SARS-CoV-2. It is likely that the pathogen was previously involved with MERS-CoV bat More recently than scientists thought.

But finding a direct ancestor of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus is very unlikely, according to scientific researchers at the University of California, San Diego, US, who conducted a comparative study of the genomes of bat species living in Asia.

Find out that file genome The complete signatures of SARS-CoV-2 and several closely related bat viruses indicate that they share a common ancestor many decades ago. But viruses are known to exchange fragments of RNA with each other, a process called recombination, so each section has its own evolutionary history.

The study was presented at the Seventh Global Health Conference, which was held in Singapore a few days ago. Scientists compared parts of the genomes of the coronavirus. Analysis indicates that some divisions of coronaviruses from bats and SARS-CoV-2 They shared a common ancestor as recently as 2016, just three years before the pathogen appeared in people in late 2019. The work has not yet been reviewed.

The researchers said in an interview with the journal that the results reduce the time between the ancestor of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that originated in bats and the transmission of the virus to humans. nature. However, it does not explain how this jump occurred, an enduring puzzle of the pandemic in which many scientists agree an animal may have intervened as a mediator.

The study highlights how difficult it is to find a direct ancestor of SARS-CoV-2 in bats, given the frequency of recombination of coronaviruses and the elapsed time. The chances of finding a direct ancestor are “close to zero,” said Edward Holmes, an evolutionary virologist at the University of Sydney, Australia.

The analysis presented in Singapore, said Joel Wertheim, a molecular epidemiologist at the University of California, San Diego, who was one of the authors of the book.

He cautioned that sampling bats for coronaviruses could identify more closely related viral fragments than those found in previously known coronaviruses, but would likely not reveal a direct ancestor.

Since the pandemic began, many researchers, especially in Southeast Asia, have sequenced coronaviruses found in bats and other mammals. They also sequenced coronaviruses in old tissue samples stored in freezers in hopes of finding the origins of the pandemic virus.

But scientists have had difficulty finding a key virus for SARS-CoV-2. This has led to speculation that the epidemic was caused by a virus that accidentally escaped from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, located in the city where the epidemic began. This lab has worked with related coronaviruses.

To date, more than a dozen viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2 have been isolated from bats and pangolins. To determine their relationship to SARS-CoV-2, researchers typically compare their entire genomes, for about 30,000 nucleotides.

Using this method, the closest known relative of SARS-CoV-2 was found to be a bat virus found in Laos called BANAL-52, whose genome is 96.8% identical to SARS-CoV-2, and a virus called RaTG13, found in Yunnan, southern China, 96.1% identical. A difference of 3-4% between their genomes and that of SARS-CoV-2 indicates that there have been about 40-70 years of evolution since these viruses shared a common ancestor.

But the researchers say that comparing whole-genome sequences ignores the role of recombination in the evolution of viruses. Some RNA segments may be very different from SARS-CoV-2, indicating that they are more closely related, while other similar segments indicate a closer relationship.

To calculate the reclassification, the researchers compared 18 bat and pangolin viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2, and divided them into 27 chunks. Each fragment — from a few hundred to a few thousand nucleotide sequences — has a different evolutionary history, said Spyros Lytras, an evolutionary virologist at the University of Glasgow, UK, who presented the work in Singapore.

For each fragment, the researchers used a larger subset of 167 related viruses to estimate how long SARS-CoV-2 shared a common ancestor with a bat or animal virus. The work was described in a post on the virological.org discussion forum last month, and the co-authors plan to submit it to a journal early next year.

Analysis revealed that some parts share a common ancestor with SARS-CoV-2 from just a few years ago. Most of the fragments share a common ancestor around 2007, but a small fragment, about 250 nucleotides long, may have shared a common ancestor in 2016, and another fragment of 550 nucleotides long in 2015. That is, only 3 or 4 years before humans People with SARS-CoV-2.

The smallest fragments came from bats that were sampled in Yunnan and Laos. Given the distances these viruses can travel with their bat hosts, Letras said, the analysis indicates that southern China and southeast Asia are hot spots for the ancestors of SARS-CoV-2. “It’s a clever tactic,” said Holmes. It gives you the purest indication of evolutionary time.” However, he noted, some fragments were very short, making these estimates less reliable since there are only a limited number of RNA nucleotides for comparison.

Read on:

“Beeraholic. Friend of animals everywhere. Evil web scholar. Zombie maven.”